BY MATTHEW ENG |

With AFTER THE STORM, Hirokazu Kore-eda Continues to Speak to the Soul

The Japanese auteur's new film is that rare feat: a splendidly rueful family portrait that honors the perspectives of every member.

Nothing of great magnitude occurs in Hirokazu Kore-eda’s After the Storm. There are no decisive partings or reunions. No blowups or breakdowns. No deaths, at least not seen onscreen. One could even argue that the small but specific circle of relatives, exes, and coworkers at the story’s center has not changed in any truly consequential way by its conclusion.

And yet, everything somehow feels different as the credits roll on Kore-eda’s quietly lived-in spellbinder. That the sheer act of individual and interpersonal contemplation can feel so momentous over the course of two hours is a testament to the observant brilliance of Kore-eda. In After the Storm, Kore-eda has crafted a study of a single man that nonetheless has eyes in all directions, proving wondrously liberal with both its spotlight and sympathies. From an American vantage, its the type of tender, true-to-life character piece that appeared with great frequency during the maturely-refocused New Hollywood of the 1970s, but is only attempted today by classicists like James Gray and Kenneth Lonergan. That films like this are few and far between in today’s commercial and even independent American cinemas might be a source of despair were it not for Kore-eda’s continued prolificacy, which is matched only by the understated flair of his filmmaking, which entails writing, directing, and editing his own projects.

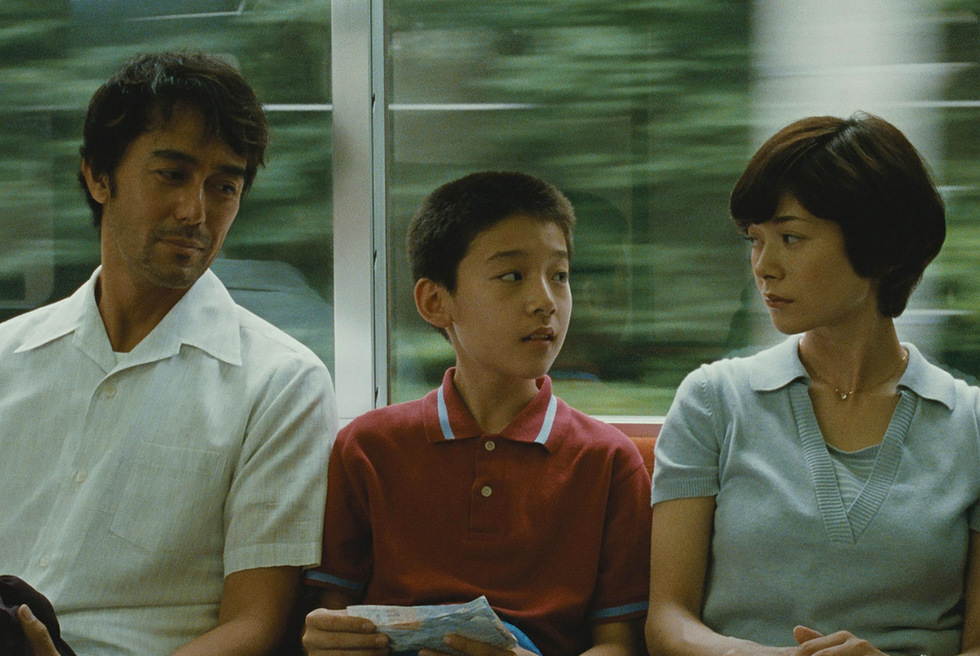

In After the Storm, Hiroshi Abe — who, like much of this ensemble, is a returning Kore-eda repertory member — plays Ryota, an absent patriarch and failed novelist who has idly allowed a lowly detective gig, once a temporary assignment taken up as research for his long-delayed next book, to become his full-time line of work. Though well into middle age, Ryota continues to be a serious work-in-progress. He has taken to spying on his estranged and exasperated ex-wife Kyoko (Yōko Maki), their sweet but not oblivious young son Shingo (Taiyô Yoshizawa), and Kyoko’s overly-alpha new boyfriend. And he’s just as liable to blow his earnings at the bike-racing track as is he is to then blackmail a high school student for some quick cash — money which should be going to Kyoko and Shingo for the latter's oft-delayed child support, but so rarely reaches them.

As embodied by the raffish Abe, with his lank frame and perpetual five o’clock shadow, Ryota remains an intensely charismatic figure. But even this undeniable charm cannot cover up his frequently humiliating faults, which remain painfully evident in the eyes of those nearest and arguably dearest to him. This group includes Shingo and Kyoko, but also Ryota's combative sister Chinatsu (Satomi Kobayashi) and, perhaps most heartbreakingly, his recently-widowed mother Yoshiko (Kirin Kiki).

After the Storm takes place not long after the passing of Ryota’s dad, who looms over the film as an imperfect but stable persona for Ryota to equal and hopefully one day surpass. We’ve seen this thematic thread before: the legacy of the deceased father as a veiled but potent phantom in the mind of the still-living son. But Kore-eda never foregrounds this element, refusing the oppressively funereal tone that usually accompanies this storyline for a mood far more ingrained in the casual comedies and mini-dramas of everyday life.

If we’ve seen the father-son through-line in past films then we’ve also certainly seen the archetype that Ryota represents: the flailing, modern man-child, reliable only in his unreliability and toxically trapped in his harmful ways, yet striving to be a better man in spite of himself. Here, too, Kore-eda avoids the trappings of a much lesser drama (or comedy, for that matter) by keeping his directorial and writerly touch almost radiantly light.

In doing so, he ensures that After the Storm is ultimately not a dreary dissection of a desperate, untrustworthy personality but a textured snapshot of a moment in time, one that encompasses the experiences of his protagonist but extends to those of other persons as well. Although intimately attached to Abe, Kore-eda's camera locates so many different individuals in the day-to-day passages of Ryota's life that the film could seemingly pick up with any one of these other "minor" characters and craft a stand-alone feature equally rich in detail and emotional dynamism. Kore-eda is aided in this endeavor by the simple but elegant cinematography of recurring collaborator Yutaka Yamazaki, who lingers on every single face and corner of Ryota’s world, from cluttered apartments and anodyne workspaces to tiny ramen huts and neon-bathed sex hotels, in addition to the succulent food shots that have become hunger-inducing staples in Kore-eda’s canon.

Yamazaki also excels with After the Storm’s major set piece — if one can even use “set piece” as a descriptor within Kore-eda’s decidedly low-key cinema. At the outset of the film, in a dialogue-driven prologue featuring Ryota’s mother and sister, we learn that there have been 23 typhoons in Japan over the course of a single year. When the 24th fortuitously strikes with a vengeance during the film’s third act, it gathers together four major characters in Yoshiko’s cramped apartment for a series of lengthy, skillfully-framed, and dexterously-edited conversations in which key relationships shift and time magically stands still. Each character becomes attuned to the needs and pains of others, if only fleetingly, in this exceptionally reflective passage, which also foregrounds what might be the finest triumph in a film full of considerable wonders.

The performances of After the Storm are indeed exceptional across the board, including pitch-perfect leading man Abe, as well as Maki, who distinguishes her bitter divorcée role with a crusty, steely impatience. But no actor shines quite as bright as the spry and superb Kiki, a Kore-eda veteran who enacted a similarly soulful mother-son bond with Abe in the master’s earlier Still Walking. Kiki is once again the heart of the movie, inhabiting her buoyant but regretful matriarch with a naturalism that’s almost invisible to the naked eye. This is an unadulterated form of being-as-acting that approaches something like sublimity in one beautifully-written, teary-eyed heart-to-heart between grandmother and grandson near the film’s end.

In this scene and so many others, Kiki also proves herself as the actor most adept at embodying the themes of Kore-eda’s film. In one crucial exchange with Abe, Kiki discusses the tangerine tree that sits firmly on her terrace, a plant that she insistently continues to water even though it no longer grows. This metaphor for Ryota’s own stunted maturation might come across as impossibly blunt or hokey in the mouth of any other actress. But through Kiki’s delicate yet stirringly sure-hearted delivery, the bittersweet truth of the line manages to reach our heads and our hearts. By the end of this exquisite performance and the illuminating film that contains it, we have come to fully understand why so many women of a certain age cannot help but nurture the ones they love, even when these same loved ones routinely fail to live up to their expectations. The harshness of reality may simply outweigh their hope for the best. But, as After the Storm so eloquently reminds us, there is always the possibility of growth.